Introduction: A Stone Relic from Chenla’s Dawn

Imagine a ridge in southern Laos, where the Phu Khao mountain looms like a silent sentinel, its peak a natural liṅga piercing the sky. Below, nestled on an unstable talus slope, lie two small sandstone cells stand, rugged, unadorned, tilted by time and earth. The megalithic site of Vat Phu is more than mere ruins; they’re the earliest mention of Khmer stone architecture, a bridge from prehistory to the grandeur of Angkor. Let me take you to Vat Phu, the cradle of Chenla, to peel back the layers of these megalithic remains. This is a site far beyond stones, it’s about spirits, blood, and the birth of a civilization. What drove the Khmer to carve these slabs? How do they tie to the animistic cults of the anak ta? Let’s walk this sacred ground, my friend, and let Gabel’s work light the way.

Chey, 7. Trapeang Kuk, 8. Koh Ker, 9. Preah Net Preah, 10. Kok Phanom Di, 11. An Lợi-Gò Tháp

Vat Phu: The Heart of a Ritual Landscape

Picture Vat Phu, perched at 14.848725°N, 105.81464°E, where the Mekong plain stretches east and the Phu Khao range guards the west. Gabel, one the academics that studied this site states in his 2022 introduction: “a site sacred since prehistory, its spring a lifeblood, its talus a stage for the oldest Khmer stoneworks”.

Two cells, simple called Cell I and Cell II stand as survivors, built from massive sandstone slabs, their simplicity a stark contrast to later Khmer temples. Gabel argues they’re not pre-Angkorian relics but protohistoric, predating the Indian-influenced towers of the 6th century. Their story begins with the anak ta, tutelary spirits of the land, and a cult tied to human sacrifice, a practice reverberating through Chinese annals and local lore.

This isn’t just a temple site; it’s a ritual landscape. The spring drew prehistoric pilgrims, the mountain’s liṅga and breast-like uroja shape captivated the Cham, and the Khmer wove it all into a sacred tapestry. From Kurukṣetra-Śrestapura to Liṅgapura, Vat Phu grew into Chenla’s spiritual and political core. But these cells? They’re the genesis, raw, megalithic, and rooted in a world before Hindu gods claimed the stage.

The Megalithic Cells:

Khmer Stone Architecture Begins

Cell I: A Timber Echo in Stone

background are visible the

serpent stairs. View towards

south.

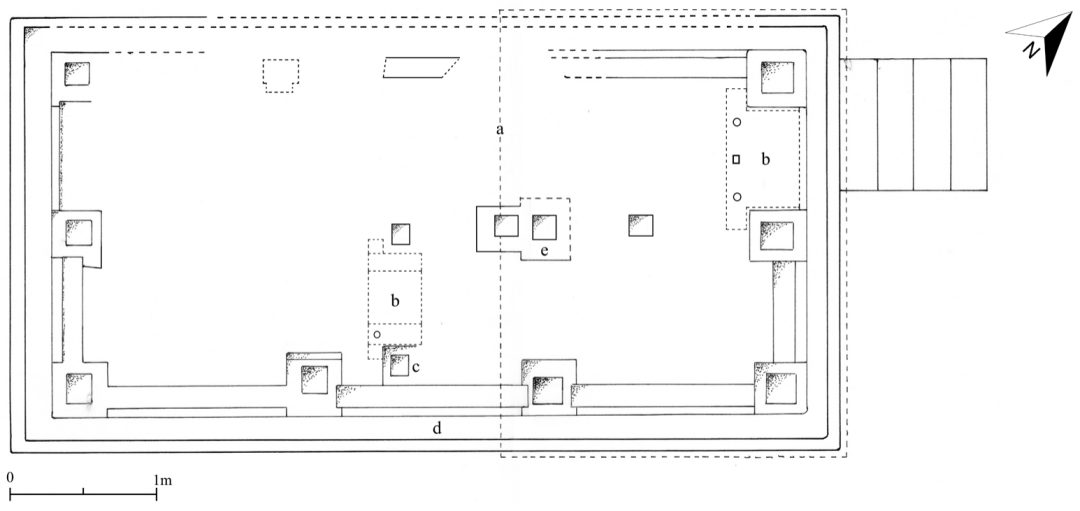

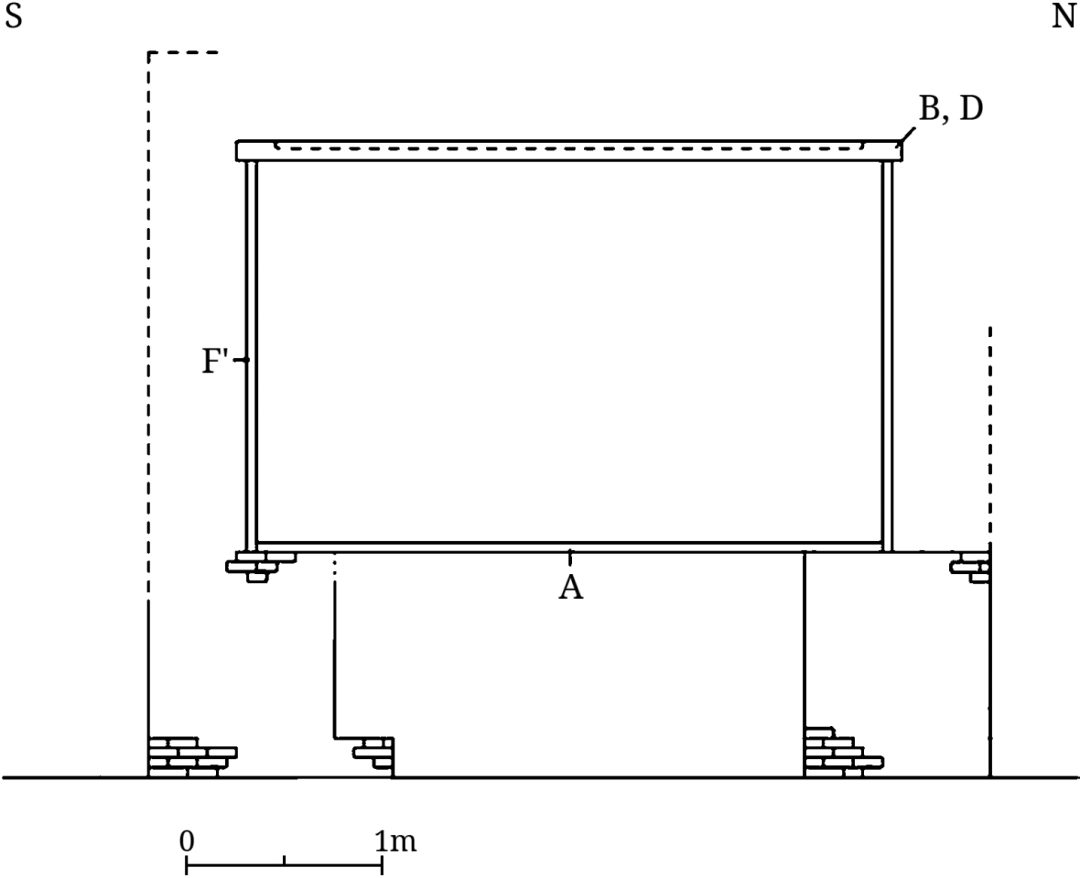

Step closer to Cell I. Gabel measures its platform at 5.66 x 2.97 meters, hewn from a boulder, its northwesterly tilt (19°) a scar from a 7th-century landslide. Five off-center steps lead to a double-door entrance. There pivots in the sill and lintel hint at wood or stone leaves. Inside, a partition splits it into two chambers, a groove rims its base, and tiny circular holes pierce the walls. No carvings, no frills, just stark utility. There we see a timber house reborn in stone, its layout mimicking stilted dwellings, its asymmetry a sign it began as an open ritual platform. Dated it to the 1st century BCE or earlier, a prototype for all that followed.

This isn’t polished craft; it’s experimental, a first stab at stone by builders versed in wood. Academics tie it to Neolithic mortuary chambers, like those at Khok Phanom Di. They are clay-floored, timber-walled, built over burials. Cell I, was a shrine for the “Lord of the Mountain,” an anak ta summoned by blood rites, its groove catching libations.

Cell II: Evolution in Sandstone

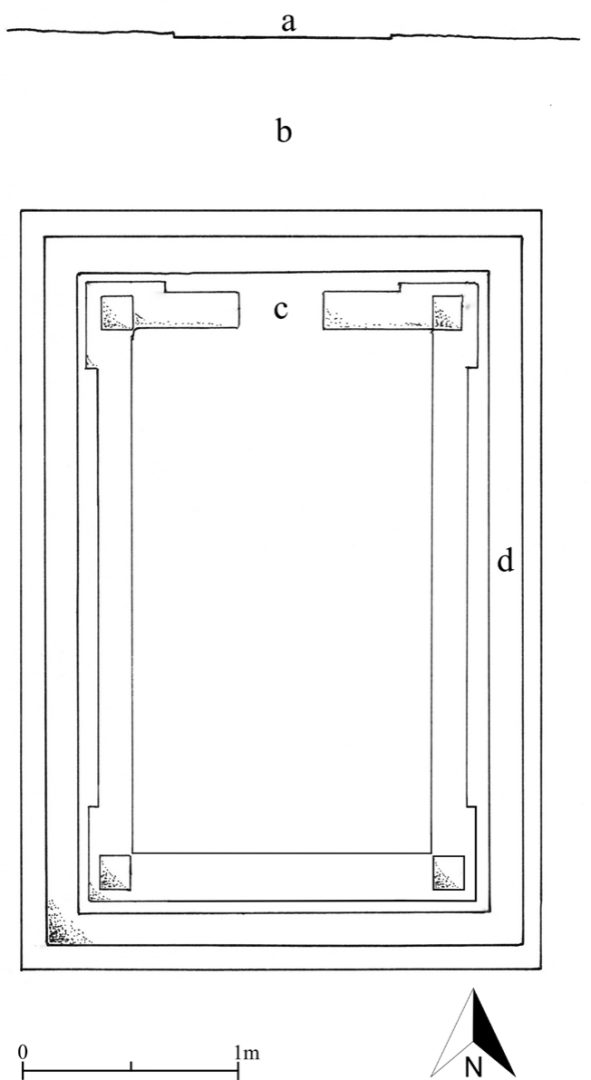

Now, still within this Megalithic Khmer stone Architecture, we find Cell II, 25 meters southeast, perched on a boulder 4 meters high. Smaller at 3.20 x 2.35 meters. It’s tidier, presenting symmetrical steps, no internal walls, a single roof slab notched to lock with pillars. Its groove lacks an outlet, suggesting a shift in ritual. Archaeologists call it a refinement, built centuries later, perhaps by the 5th century CE, for the “Lady beyond the River.” The north orientation, shared with Cell I, ties it to the spirit realm, not Hindu cosmology. Those holes and grooves? Vestiges of a fading tradition, absent in later cells like Sambor Prei Kuk’s N17.

Gabel’s fieldwork shines here, laser measurements, photos from the 1970s versus today, showing preservation despite chaos. These Vat Phu megalithic cells, he argues, are Chenla’s architectural dawn, born of local genius, not Indian import.

Spirits and Sacrifices: Khmer Beliefs in Stone

The Anak Ta and Blood Rites

Feel the weight of the anak ta, the Khmer spirit guardians. What we know paints them as ancestors-turned-deities, dwelling in trees, hills, or stones, not as statues until Hinduism crept in. At Vat Phu, the “Lord of the Mountain” and “Lady beyond the River” reigned, their cells temporary homes during rituals. A Sui dynasty text chills the spine: a king, atop Liṅgaparvata, sacrifices a human yearly to Po-to-li (Bhadreśvara’s precursor). This is believed to be linked to Ba Phnom’s 1877 rites, where blood foretold rain, suggesting continuity from protohistory to the 20th century.

The crocodile carving and serpent stairs, the tilted relics near Cell I, embody this cult. The crocodile is recognized as Kron Pali, earth’s creator, escorting souls across rivers. The serpents, pre-nāga, symbolize fertility, their lotus grafts a Cham echo. These weren’t decor; they were ritual hardware, channeling blood into grooves or basins.

From Animism to Hinduism

Enter king Devanika, 5th-century harbinger of Śiva-Bhadreśvara. Here a we find a Cham interlude, the liṅga and uroja of Phu Khao drawing pilgrims, yet the Khmer reclaimed it by 590 CE under Citrasena. The animistic core endured, then Hinduism layered over it, not erasing it. Post-cataclysm, a brick cella rose near the spring, aligning east, its praṇāla channeling sacred water. Gabel dates this shift to Íśānavarman I’s reign (616–628 CE), when Sambor Prei Kuk eclipsed Kurukṣetra-Śrestapura.

Beyond Vat Phu: A Wider Canvas

Oc Eo’s Cell K: Funan’s Parallel Path

Shift to Oc Eo, Funan’s port. The site studies resurrected Cell K from Malleret’s 1959 notes, granite slabs, 3.15 x 2.75 meters, atop a U-shaped brick wall. No holes, no groove, just a shaft below, hinting at a tomb-turned-shrine. He dates it to 200 BCE, rooted in Hang Gon’s cist tomb (§148), a granite box with a pillared hall, circa 500 BCE. Unlike Vat Phu’s timber lineage, this is stonecraft’s raw infancy, a Funan outlier that didn’t spread.

indicating an indentation.

Preah Net Preah and Beyond

At Preah Net Preah, 300 kilometers west, we find echoes of Vat Phu, a hollow crocodile basin, serpent-flanked steps, all archaic, pre-Hindu and tied to water rites. As we scan Southeast Asia, we find Zothoke’s aquatic carvings, Koh Ker’s Trapeang Khna reliefs. These clusters, he argues, mark a shared a megalithic protohistoric reverence for animal spirits, predating Indian iconography.

Vat Phu a Legacy in Stone: From Cells to Temples

Gabel one of the main academics that researched Vat Phu, traces the cells’ ripple: rectangular plans linger in pre-Angkor brickwork, as in, Sambor Prei Kuk’s S1, Phimeanakas, pilasters mimic pillars and pedestals shrink cells into miniatures. By the 8th century, square plans and Indian decor dominate, but Vat Phu’s DNA persists. He concludes: these megalithic cells, born in Chenla’s heart, shaped Khmer architecture for centuries, a testament to a spirit-driven past.

Conclusion: Vat Phu’s Eternal Echo

So, this is where we stand: Vat Phu, born of the Megalithic Khmer Stone Architecture, where this craft first spoke for the Khmer, rooted in timber and tombs, anointed by blood and spirit. Cell I and II aren’t footnotes, they’re the prologue, whispering of a time when the anak ta ruled, before Śiva and Viṣṇu claimed the stage. What’s next? More digs, perhaps, to unearth the prehistoric terraces Gabel suspects are there. For now, Vat Phu stands as Chenla’s crucible, its stones a bridge to a lost world. You’ll only find unique sites like this at AncientHistoryX.