Archaeologists led by Ruth Shady have traced how Caral—the earliest known civilization in the Americas—adapted to a severe drought about 4,200 years ago. Instead of collapsing into violence, people moved from the Supe Valley hub of Caral to nearby centers like Vichama (coast) and Peñico (inland), carrying their ideology, architecture, and trade networks with them. Their reliefs and murals record famine, hope, rain symbolism, and civic memory.

A Climate Shock—and a Strategic Move

New fieldwork indicates a prolonged drought forced the abandonment of Caral’s core and the resettlement to multiple nodes better positioned for fishing, river-valley farming, and exchange. Vichama’s coastal economy and Peñico’s inland location show an intentional spread of risk rather than a single-site failure.

Vichama’s Friezes: Famine, Rain, Renewal

At Vichama, wall reliefs depict emaciated bodies, pregnant women, ritual dancers, and a toad struck by lightning—iconography associated in Andean thought with rainfall and agricultural rebirth. These scenes appear to memorialize scarcity while signaling hope that water returns.

Peñico: Continuity Without War

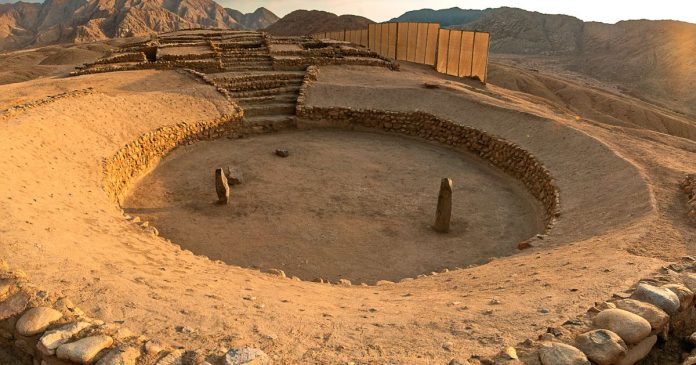

Peñico (ca. 1800–1500 BC) mirrors Caral’s planning—circular plazas, decorated temple architecture—and reveals no clear evidence of conflict. Finds include conch-shell trumpets (pututu), jungle animal remains routed across the Andes, and elite male and female figurines, suggesting both wide trade and ideological cohesion.

Trade Webs and Civic Ideology

Material coming from coast, highlands, and rainforest—fish bones, Spondylus shells, macaque and macaw remains—attest to resilient supply lines. Symbolic instruments (pututu) and formal plazas reinforce a shared political-religious order that outlived the drought by relocating it.

Caral’s response complicates the common “collapse” story. Here, climate crisis produced mobility, memory-keeping, and institutional continuity rather than warfare—showing societal sophistication in the Americas contemporary with Egypt and Mesopotamia.

Sources

The Guardian: overview of the new synthesis on Caral’s climate adaptation and the Vichama/Peñico evidence.

Arkeofili (TR): summary with quotes from project leaders and context for Vichama and Peñico.

Reuters & Archaeology/Archaeology Magazine: on Vichama’s toad imagery and climate symbolism (corroborating the rainfall/fertility reading).

Reuters/Smithsonian/The Times: Peñico’s excavation details, chronology, and public opening in 2025.

If you like this story check out : Huaca Yolanda: Gobekli Tepe of the Americas Unearthed