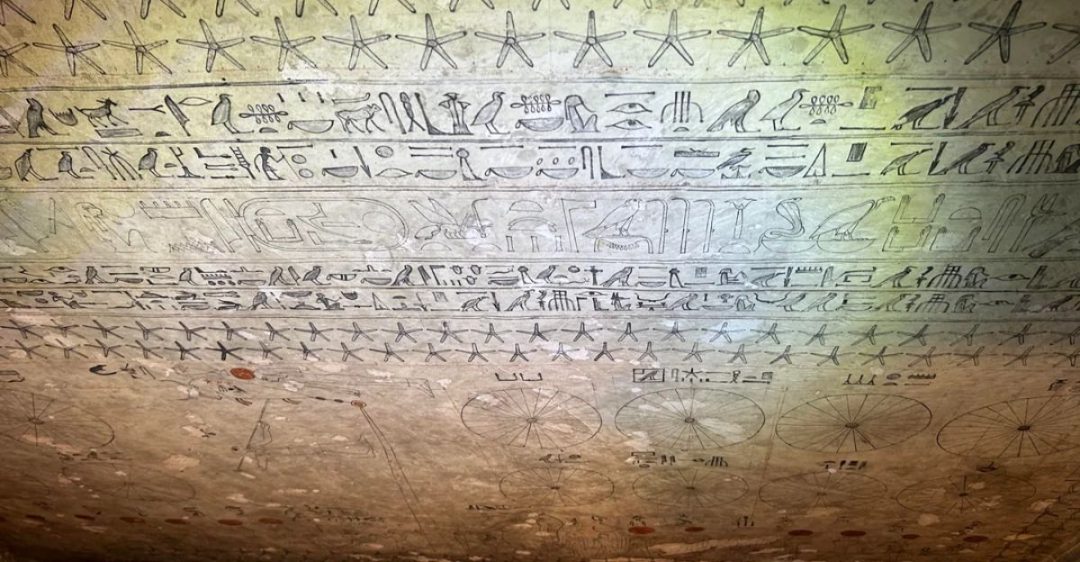

Senenmut’s star map, adorning the ceiling of Theban Tomb No. 353 near Deir el-Bahri, Egypt, stands as one of the most enigmatic artifacts of antiquity. Unearthed in 1927 by Herbert Winlock, this celestial masterpiece from the 18th Dynasty (circa 1478–1458 BCE) continues to captivate archaeologists, astronomers, and historians. Crafted during the reign of Queen Hatshepsut, the map blends astronomy, mythology, and ritual, offering a window into ancient Egypt’s cosmic worldview. This article delves into the mysteries of Senenmut’s star map, exploring its design, cultural significance, and the riddles that keep scholars guessing. From missing planets to cryptic symbols, this ancient chart invites us to unravel a cosmic puzzle that challenges our understanding of early astronomy.

Senenmut: The Man Behind the Map

Senenmut, born to provincial parents Ramose and Hatnofer, rose from obscurity to become a towering figure in Hatshepsut’s court. Holding nearly 100 titles, including “Steward of the God’s Wife” and tutor to Hatshepsut’s daughter, Neferu-Re, he was a master architect and possibly an astronomer. His tomb, a 97-meter-long, 41-meter-deep hypogeum near Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple, reflects his prestige. Yet, its unfinished state and partial destruction raise haunting questions. Why was it abandoned? Did Senenmut’s proximity to power lead to his downfall? Some speculate a romantic tie with Hatshepsut, though no evidence supports this. His disappearance after her reign, coupled with the tomb’s defacement, adds a layer of intrigue. The answers may lie in the celestial ceiling, where Senenmut’s star map holds court.

A Celestial Canvas: The Star Map’s Design

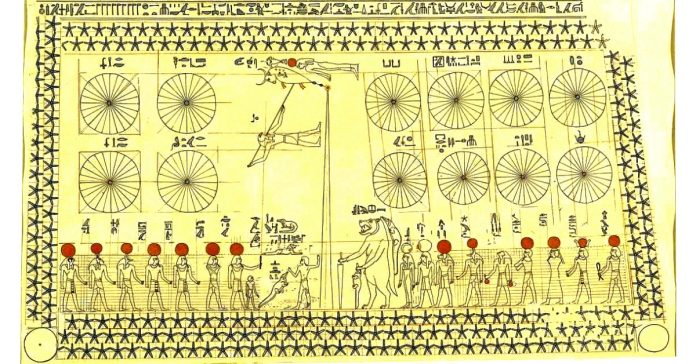

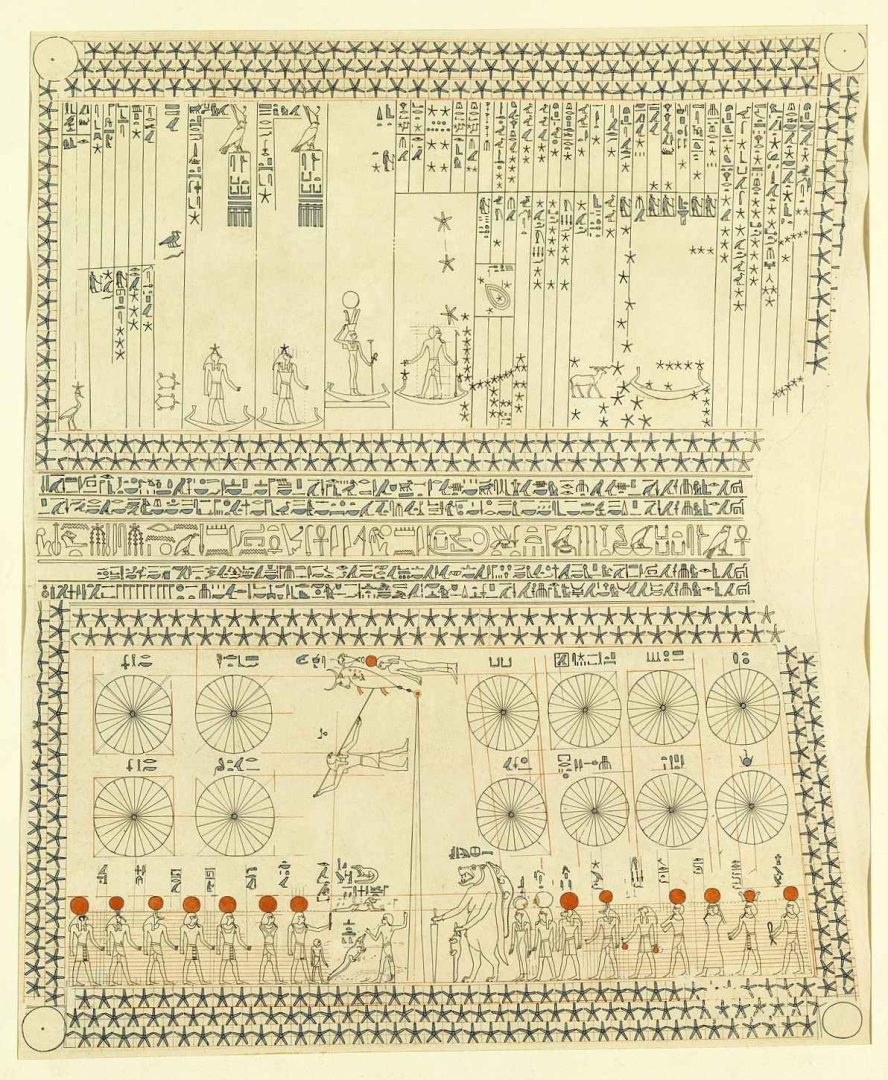

Senenmut’s star map, painted around 1470–1450 BCE, captures the night sky as seen from Thebes. Unlike modern star charts, it prioritizes symbolism over precision, weaving astronomy into Egypt’s spiritual and mythological fabric. The ceiling divides into northern and southern sections, each rich with celestial imagery.

The northern section features Ursa Major, known as the “plough,” alongside 12 circular “wheels” grouped into sets of 4 and 8. These wheels, appear uniform, sparking debate about their purpose. The southern panel showcases 36 decans—star groups rising every 10 days for timekeeping. The decans flank constellations like Orion (linked to Osiris) and Canis Major. Planets such as Jupiter, Saturn, Mercury, and Venus sail across the sky in boats, a poetic nod to their celestial journey. The map’s artistry reflects Egypt’s belief in the heavens as a divine realm. The map has curious anomalies, however. The map is missing planets, has cryptic inscriptions, and curious alignments, which fuel endless speculation.

The Lunar Wheels: A Ritual Enigma

The maps “wheels” cut to the heart of the it’s mystery. These 12 circular motifs, each paired with hieroglyphs, likely represent the 12 lunar months of Egypt’s civil calendar, not specific moon phases. Their uniform design raises doubts about their astronomical precision. Scholars suggest the hieroglyphs, though damaged, reference rituals like “First Day of the Month” or “Appearance,” invoking deities such as Thoth (god of wisdom and time) or Khonsu (a moon god). The inscriptions’ repetitive nature emphasizes Ma’at, the principle of cosmic order.

Why the split into 4 and 8 wheels? Some propose it reflects seasonal divisions or festival clusters, while others see it as a processional order tied to lunar ceremonies. The lack of phase-specific imagery suggests a symbolic role, perhaps marking sacred moments rather than tracking the moon’s waxing and waning. Could these wheels be part of an unfinished timekeeping system, possibly linked to the Ramesside star clocks developed around the same period? The absence of clear translations (due to erosion and limited documentation) keeps this question open, making the wheels a tantalizing puzzle within Senenmut’s star map.

The Missing Mars: A Cosmic Conundrum

One of the map’s most perplexing features is the absence of Mars among the planets. Jupiter, Saturn, Mercury, and Venus appear in boats, but the red planet is conspicuously missing. Scholars dismiss theories that this reflects a specific night when Mars was invisible. Instead, they propose an iconographic explanation: the map may draw from clepsydra (water clock) designs, where Mars was similarly omitted, perhaps due to artistic or cultural choices.

Adding to the mystery, Saturn’s usual title, “Horus, the Bull of Heaven,” is replaced with “Mother of the Bull of Heaven.” This shift, possibly tied to Hatshepsut’s gender, suggests a deliberate alteration. Was Mars excluded to align with a mythological narrative, perhaps elevating the sun-god “Re” (another Horus form) over the warlike Mars? Or does it hint at a ritual taboo, now lost to time? The omission, combined with Saturn’s curious renaming, makes Senenmut’s star map a cryptic text that defies easy answers.

The Winding Waterway: Mapping the Milky Way

Senenmut’s star map may also depict the Milky Way, described in ancient texts as the “Winding Waterway,” a cosmic river stretching across the sky. The goddess Nut, often shown arching over the earth god Geb with a star-studded body, could embody this galaxy, her form incorporating the “Great Rift”—a dark band of cosmic dust. This imagery casts the Milky Way as a sacred pathway for souls navigating the afterlife, blending astronomy with spiritual symbolism. The map’s integration of such a galactic feature suggests a sophisticated understanding of the cosmos, far beyond what historians once assumed about early civilizations.

Was this depiction a literal star map or a metaphorical guide for the dead? The interplay of Nut’s imagery and the Winding Waterway hints at both, deepening the map’s enigmatic allure. Its influence on later Egyptian celestial art, seen in Greco-Roman zodiacs, underscores its lasting impact.

The Hyades Alignment: A Stellar Clue?

The tomb’s corridor, aligned at an azimuth of approximately 99 degrees and a 25-degree inclination, faces the rising of Aldebaran and the Hyades cluster around 1470 BCE. A four-star ovoid in the southern sky, dubbed the “Asterism of Water,” might represent the Hyades, suggesting intentional design. Did Senenmut align his tomb to this star cluster, tying his eternal rest to a celestial event? The possibility is tantalizing, but the lack of definitive evidence—compounded by damage to similar depictions in other artifacts like the Karnak clepsydra, keeps this alignment a mystery. If deliberate, it would elevate Senenmut’s star map to a monument of cosmic precision.

Debates and Interpretations

Scholars remain split on the map’s purpose. Some view it as a practical tool for tracking agricultural and ritual cycles, with decans and lunar wheels guiding timekeeping. Others see it as a symbolic tableau, reflecting Egypt’s afterlife beliefs and cosmic order. Your focus on the wheels’ uniformity highlights a key tension: their repetitive design suggests ritual over observation, yet their hieroglyphs, fragmentary and elusive, hint at deeper meaning. References to offerings or deities like Thoth appear, but full translations remain out of reach due to erosion and limited documentation.

The map’s anomalies, like the erased lion and crocodile sketches beneath a “standing man” figure add further intrigue. Was this an artistic error or a deliberate shift in cosmic symbolism? Could it reflect an early draft of a timekeeping system, perhaps pioneered by Senenmut himself? These questions keep the map’s purpose shrouded in mystery.

Cultural and Astronomical Context

Ancient Egyptian astronomy wove together religion, agriculture, and timekeeping. Using tools like the merkhet and gnomon, Egyptians tracked stars to develop a 12-month civil calendar with five epagomenal days. Constellations like Orion (tied to Osiris) and the Big Dipper (the “plough”) linked the heavens to seasonal and mythological cycles. Senenmut’s star map, with its decans, planets, and lunar wheels, embodies this integration, serving as both a spiritual guide and a cultural artifact. Its influence persisted for over 1,500 years, shaping celestial art through the Greco-Roman period.

Comparing Ancient Star Maps

Senenmut’s star map stands out among ancient celestial depictions. Sumerian maps from 5000 BCE are basic, lacking cultural depth. Babylonian maps from the 2nd millennium BCE focus on astrology, while Greek maps from the 5th century BCE, like those in Ptolemy’s Almagest, are systematic but later. Paleolithic maps, up to 40,000 years old, are speculative and rudimentary. Senenmut’s map uniquely blends myth and observation, reflecting Egypt’s spiritual cosmology in a way unmatched by other cultures.

A Legacy of Cosmic Wonder

Senenmut’s star map challenges assumptions about ancient knowledge, revealing a civilization that saw the stars as divine guides. Its lunar wheels, missing Mars, and possible Hyades alignment suggest a deeper understanding of the cosmos than once thought. The tomb’s unfinished state and Senenmut’s mysterious fate—his tracks vanishing after Hatshepsut’s reign—add a layer of intrigue. Did he encode a secret in the ceiling, perhaps tied to his fall? The map’s influence on later Egyptian star charts underscores its enduring impact.

Decoding the Celestial Riddle

Senenmut’s star map is a cosmic enigma, blending astronomy, mythology, and mystery. Its lunar wheels, with their cryptic hieroglyphs, may mark sacred months but defy clear explanation. The absence of Mars and the altered Saturn title hint at hidden stories, while the Hyades alignment suggests cosmic intent. The lack of scholarly consensus only heightens the fascination. Was this map a practical tool, a spiritual guide, or a coded message from a man at the edge of power?