A new archeoastronomy study in the Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage; redefines our understanding of the ancient Egyptian Sky Goddess Nut. Researcher Or Graur explores how Nut’s depictions on coffins might reveal the earliest visual evidence of the Milky Way. This discovery challenges long-held assumptions and links ancient Egyptian cosmology to celestial wonders observed worldwide. Graur’s work, rooted in a detailed analysis of ancient artifacts, offers a fresh perspective on how the Egyptians perceived their sky goddess in relation to the galaxy.

The study’s significance extends beyond Egypt, drawing parallels with indigenous cultures such as the Navajo, Hopi, and Zuni. Graur’s findings suggest a universal human fascination with the Milky Way. Expressed through art and mythology across continents. This cross-cultural connection enhances our understanding of ancient astronomical knowledge. Positioning Nut as a central figure in a global narrative. As the research unfolds, it invites scholars and enthusiasts to reconsider the interplay between mythology and the cosmos.

Graur’s Journey into Ancient Skies

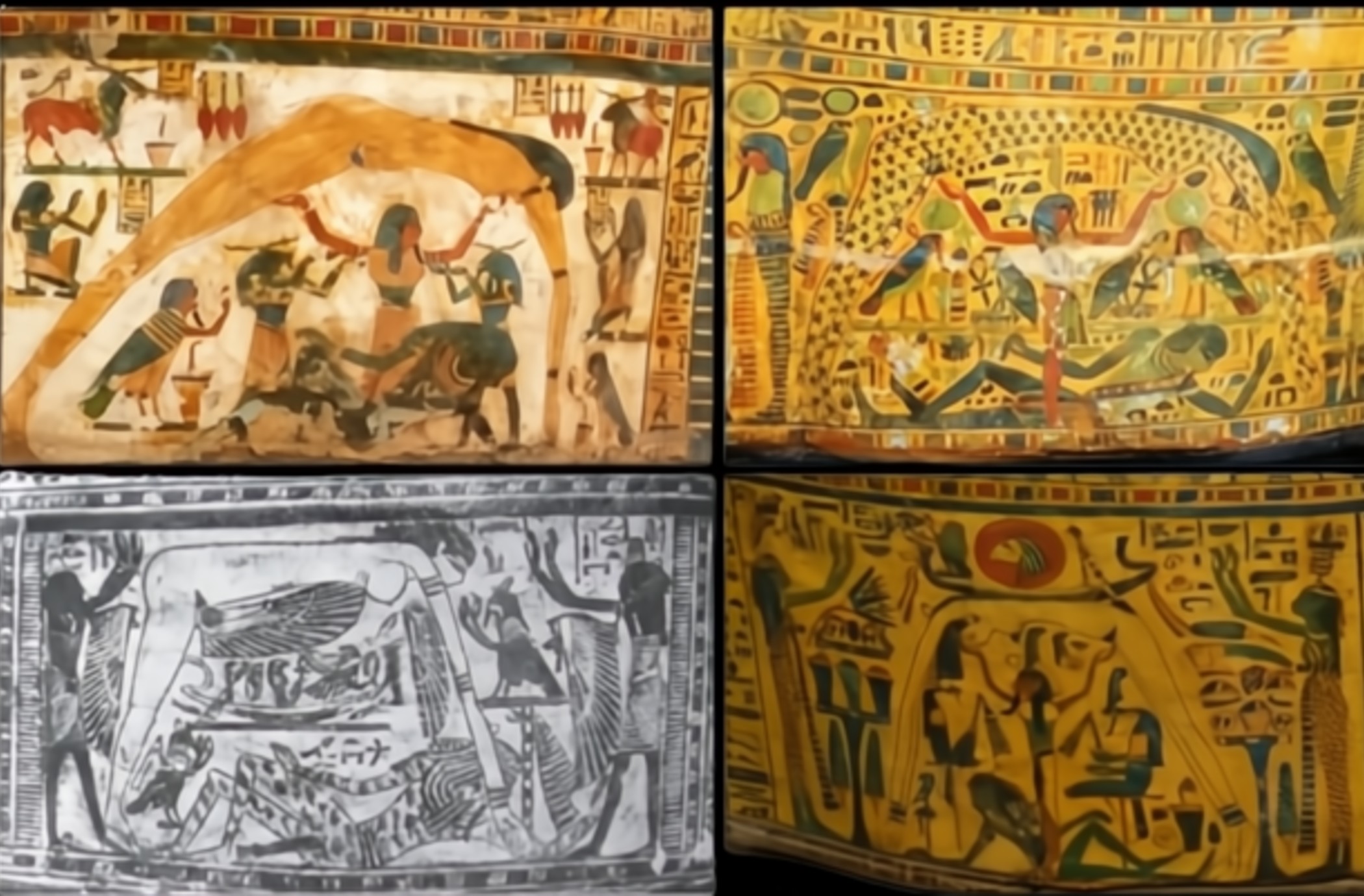

by Shu and arched over a green-colored Geb (courtesy: Museo Egizio); (b) C84, a typical example in which Nut

is covered in stars (courtesy: Rijksmuseum van Oudheden); (c): C89, Nut swallowing and giving birth to winged Sun discs (courtesy: Turaev, 1914); (d) C94, Nut carrying the Sun in the Solar Bark (courtesy: Museum

Gustavianum)

The Researcher’s Quest

Or Graur embarked on a meticulous quest to decode Nut’s celestial role. He analyzed 555 coffin elements. With a focused examination of 118 cosmological vignettes from the 21st and 22nd Dynasties. His approach combines archaeological precision with astronomical insight. Building on his 2024 paper where he proposed a symbolic, rather than identical, relationship between Nut and the Milky Way. This foundation drives his current exploration, blending disciplines to uncover hidden meanings.

Methodology and Data Collection

Graur’s methodology involved scouring digital collections from major museums such as the Louvre and British Museum. Supplemented by printed catalogs and scholarly works. He ensured each coffin included detailed imagery from all angles to confirm Nut’s presence. Creating a robust dataset despite its limitations. The catalog, though not exhaustive, highlights a peak in cosmological vignettes during the 21st and 22nd Dynasties. Reflecting a cultural shift toward celestial symbolism. His dedication to this interdisciplinary study sets a new standard for research in ancient history.

A Unique Discovery on Nestaudiatakhet’s Coffin

Archaeological Museum

The Standout Feature

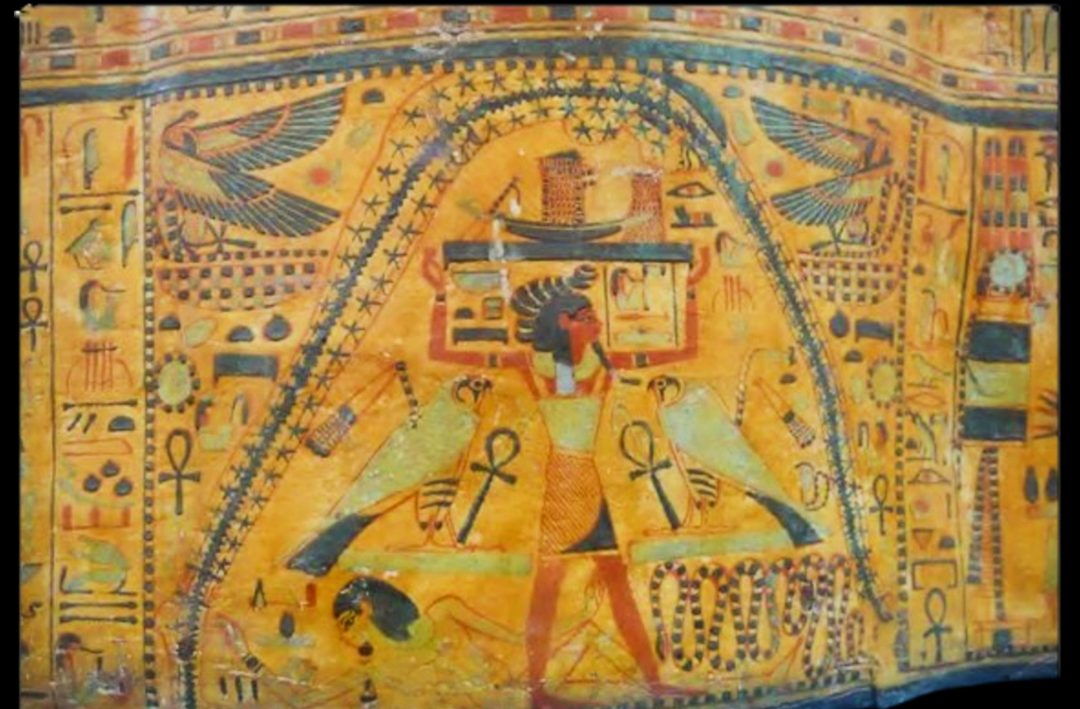

The study highlights a standout feature on the outer coffin of Nesitaudjatakhet, where a thick, undulating black curve bisects Nut’s star-studded form. This design echoes the Great Rift, a dark band that splits the Milky Way, offering a visual link to the galaxy. Graur notes similar undulating patterns in the astronomical ceiling of Seti I’s tomb and along Nut’s back in the tombs of Ramesses IV, VI, and IX. This consistency suggests intentional representation, marking a pivotal moment in identifying the Milky Way in ancient art.

pattern running along Father Sky’s arms and shoulders (courtesy: Joe Ben, Jr; from the author’s

collection).

Cross-Cultural Parallels

The curve’s resemblance extends beyond Egypt, aligning with depictions of the Milky Way in Navajo, Hopi, and Zuni spiritual beings. These parallels indicate a shared human effort to map the night sky through cultural symbols, with Nut serving as Egypt’s celestial interpreter. Graur argues this feature supports the idea that the Egyptians visualized the Milky Way as cleaving the sky, a concept reinforced by its rare appearance on Nesitaudjatakhet’s coffin. This discovery reopens the possibility that “Winding Waterway” might be the ancient Egyptian name for the galaxy.

Nut’s Role in Egyptian Afterlife and Cosmos

(C121), Nut is colored blue and studded with stars (courtesy: Louvre E3913; © 2020 Musée du Louvre, Dist.

GrandPalaisRmn / Christian Décamps).

Nut played a vital role in guiding the deceased to the afterlife, a theme etched into coffin art since the Old Kingdom. Spells from the Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts depict her shielding souls with her arms, reassembling bones, and guiding them skyward. Graur connects this protective imagery to the Milky Way’s visibility during winter months, proposing it symbolized her celestial embrace. Her role as a ladder or outstretched figure in these texts strengthens this astronomical link, blending mythology with observable phenomena.

Celestial Cycles and Protection

In cosmological vignettes, Nut’s arched posture reinforces her identity as the sky, protecting Earth from the void’s waters. These depictions often show her swallowing the sun at dusk and birthing it at dawn, a cycle tied to the netherworld Duat. Graur highlights her interaction with decan stars, used as a night clock, as further evidence of her celestial governance. This multifaceted role underscores her importance in both daily life and the afterlife, making her a bridge between the earthly and divine.

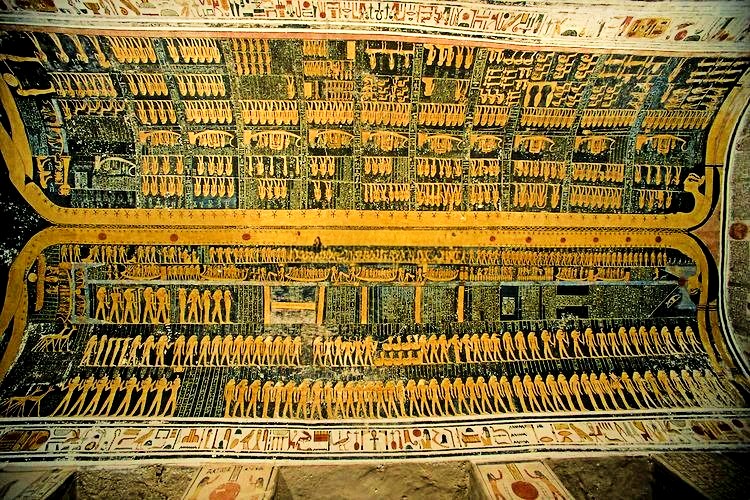

Depiction in Ramesses VI’s Tomb

In the tomb of Ramesses VI, Nut’s arched form graces the Book of the Day, a celestial narrative on the burial chamber’s ceiling. She embodies the sky, adorned with stars and a winding curve hinting at the Milky Way. This depiction shows her swallowing the sun at dusk, guiding it through the Duat for dawn’s rebirth. Graur ties this imagery to the Milky Way’s path, visible in winter, linking her cosmic role to Egypt’s afterlife beliefs. Her presence underscores her duty as a divine protector, bridging mortal and eternal realms.

Evolution of Nut’s Depictions Across Dynasties

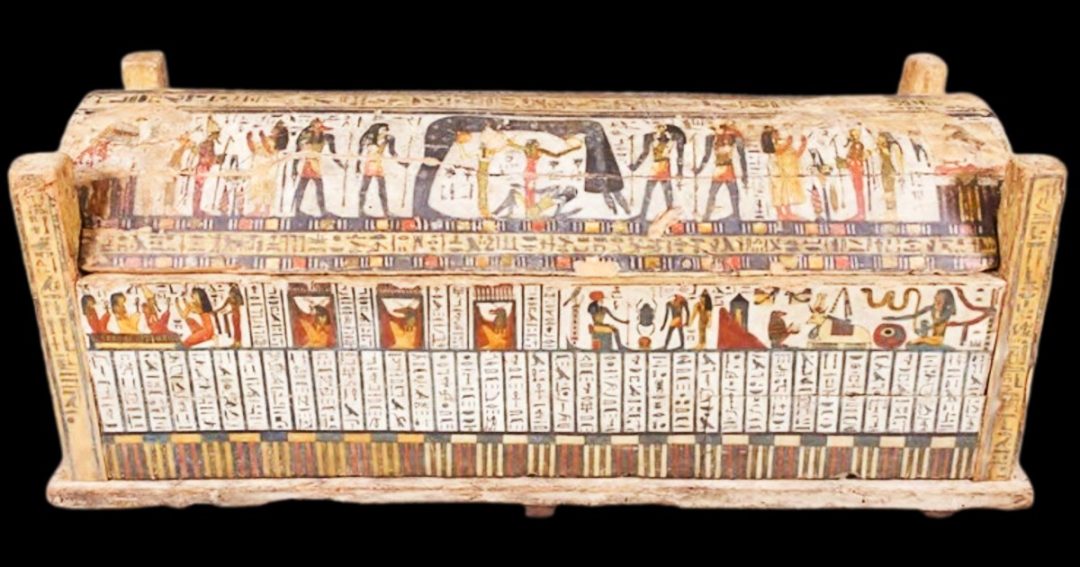

Graur’s catalog reveals how Nut’s portrayal evolved across ancient Egyptian history. Early coffins from the Old Kingdom, First Intermediate Period, and Middle Kingdom lacked her image, relying on written invocations for protection. The 18th Dynasty marked a shift, with lids featuring a vulture, possibly Nekhbet or Nut, indicating her emerging visual presence. This gradual development reflects changing artistic and religious priorities over centuries.

Emergence of Winged Forms

By the 19th Dynasty, clear depictions of Nut as a kneeling, winged goddess appeared, often named alongside her figure on coffins such as Khonsu’s. This trend continued into the 21st, 25th, and 26th Dynasties, with variations on headboards and amulets, invoking her protective spells. The 21st and 22nd Dynasties peaked with cosmological vignettes, where Nut’s star-covered form dominated, a shift Niwiński attributes to defenses against grave robbers. This evolution shows a move from text to image, enriching her afterlife role.

Later Portraits and Cultural Shifts

King Merneptah, usurped by 21st Dynasty King Psusennes I (courtesy: Egyptian Museum in Cairo J87297; image credit: CK-TravelPhotos/Shutterstock.com); 21st Dynasty inner coffin of Butehamon (courtesy: Museo Egizio 2237); 22nd Dynasty coffin of Tanetmit (courtesy: Louvre N2587; © 2004 Musée du Louvre / Georges Poncet); 25th Dynasty coffin of Tariri (courtesy: Museo Egizio 2220)

Later dynasties favored full-length portraits inside coffins, blending guardian and celestial themes. The 26th Dynasty onward saw naked, star-studded versions, incorporating Solar discs and constellations, reflecting Greek influences in Ptolemaic and Roman periods. Graur notes the redundancy of cosmological vignettes by the 21st Dynasty, with only 6% of coffins featuring full-length portraits versus 41% with vignettes. This shift highlights Nut’s enduring cosmological significance, adapted to new cultural contexts.

The Milky Way’s Symbolic Link to Nut

The undulating curve on Nesitaudjatakhet’s coffin offers a visual clue to the Milky Way’s significance in Egyptian art. Graur notes its resemblance to the Great Rift, a dark band in the galaxy, and compares it to zigzag patterns in Navajo, Hopi, and Zuni art. This similarity suggests a shared cultural effort to represent the Milky Way, with Nut serving as Egypt’s celestial canvas. The curve’s rarity strengthens Graur’s 2024 view that it enhances, rather than defines, Nut’s identity.

Linguistic and Seasonal Connections

Graur proposes “Winding Waterway” as a potential Egyptian name for the Milky Way, a hypothesis tied to the curve’s depiction. This term, if confirmed, would align with textual descriptions of Nut’s sky-spanning form, adding a linguistic layer to her celestial role. The Milky Way’s seasonal orientation, northwest to southeast in winter, mirrors texts such as von Lieven’s translation of the Fundamentals, suggesting an evolving astronomical awareness. This connection invites deeper exploration of Egyptian star lore.

A Holistic Cosmic View

The limited presence of this feature, confined to one coffin, underscores Nut’s broader sky representation. Graur argues she incorporated the Milky Way alongside the sun and stars, reflecting a holistic cosmic view. This perspective challenges earlier interpretations, such as Nut’s arms marking cardinal points, and aligns with her arched vignettes. The discovery expands Nut’s mythology, positioning her as a dynamic symbol of the ancient Egyptian sky.

A Legacy in the Stars

Graur’s work redefines Nut’s cosmic role, bridging Egyptian mythology with global astronomy. His catalog, available on request, honors contributors such as Niwiński, and museum curators who shared images and expertise. This study not only illuminates ancient skies but also sets a precedent for interdisciplinary research. The Milky Way connection to Nut endures as a testament to humanity’s timeless stargazing heritage.

The Push for Digital Preservation

The call for digitized collections resonates today, ensuring future generations access these treasures. Graur’s findings inspire ongoing exploration, linking past and present through the stars. The Milky Way’s role in Nut’s narrative highlights the enduring power of ancient art to reveal cosmic truths, inviting scholars to carry this torch forward.

Author’s Note

Nut begins as connection to the cosmos; her form esoterically connected to the Milky Way. She guides souls, embodying divine order. Her arched body weaves Egypt’s cosmic vision as above so below. But gradually, this connection wanes. Her stars fade; her role softens. By later dynasties, she stands alone, a naked figure embodying only flesh & earthly desires, not heavenly truths. This de-evolution echoes the fall of kingdoms. Toynbee sees civilizations crumble when ideals erode. Tainter notes complexity simplifies in decline. Spengler warns of spiritual loss in material ages. Nut’s Milky Way dims, overtaken by the material world. Her sacred meaning vanishes, leaving mortal shadows. This arc we see documented through the histories resonates with us today, as we search for lost truths while we lament our current state.

“We truly are a species with amnesia. We have forgotten a very important part of our story.”

― Graham Hancock