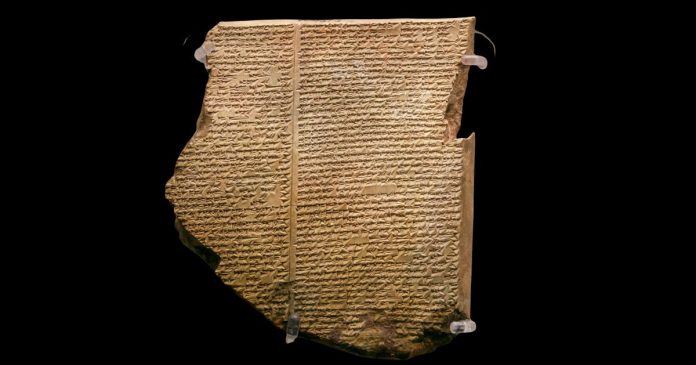

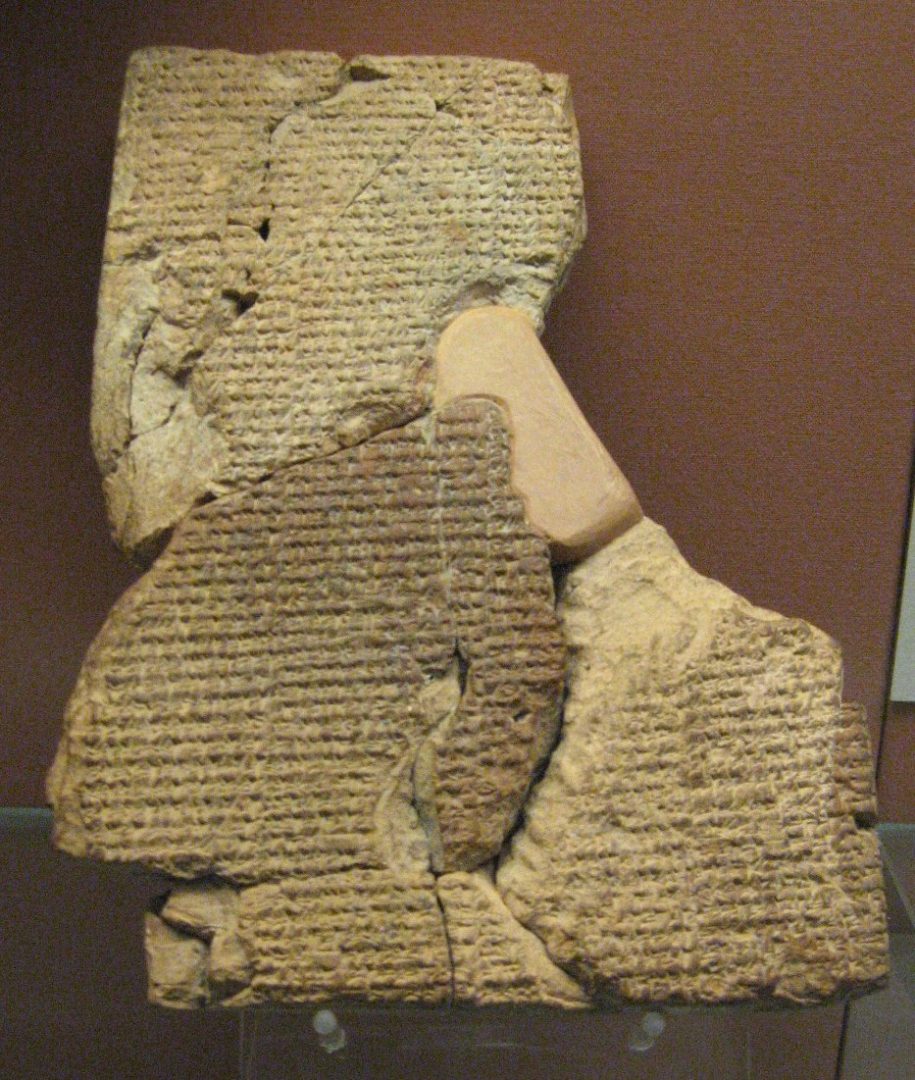

Long before the Hebrew Bible recounted Noah’s flood, ancient Mesopotamian traditions had already embedded the motif of a catastrophic deluge—one driven by divine will to purge a corrupt humanity—deep within their mythological corpus. Sumerian poets first developed this narrative, and later Akkadian scribes adapted it during the Old Babylonian period (circa 18th century BCE). The scholar-priest Sîn-lēqi-unninni eventually compiled its most complete version in the Standard Babylonian edition of the Epic of Gilgameš around the 12th century BCE.

This ancient flood narrative, preserved on cuneiform tablets and attributed to the character Utnapištim (Akkadian; corresponding to Ziusudra in Sumerian and Atrahasis in earlier Akkadian sources), stands as the oldest known written account of a deluge myth. It predates the Biblical flood story of Noah in Genesis by more than a millennium and reflects a well-developed Mesopotamian worldview in which divine-human relations were fraught with tension, judgment, and the precarious balance between destruction and mercy.

Utnapištim and the Divine Decision to Annihilate Humanity

In the Epic of Gilgameš, the gods grow increasingly intolerant of the ever-expanding human population. Their rest is disturbed by incessant noise, symbolic of humanity’s unruly behavior and unchecked ambition. The chief deity Enlil, associated with wind and royal authority, voices the most vehement opposition and ultimately calls for the extermination of mankind. This echoes similar themes found in the Atrahasis Epic, an earlier Akkadian text from the 17th century BCE, where overpopulation and societal chaos provoke divine retribution.

The proposed solution is drastic: a flood of apocalyptic proportions, designed to wipe the slate clean and restore cosmic order. Unlike in later Abrahamic versions, this decision is not couched in moral terms of sin or righteousness, but in practical terms of divine dissatisfaction with human interference.

Enki’s Intervention and the Commissioning of Utnapištim

Yet divine unanimity is not total. Enki (Ea in Akkadian), god of subterranean waters, wisdom, and creation, opposes the extermination of the human race. Bound by the divine council’s decision, he cannot overtly defy the decree, but he seeks a covert method of preserving life. In a carefully orchestrated act of subversion, Enki communicates indirectly with a pious man named Utnapištim. In some versions, this communication occurs through dreams; in others, through a whisper conveyed via the reeds of a wall—a poetic mechanism symbolizing the blurred boundary between divine knowledge and human reception.

Enki instructs Utnapištim to construct a massive vessel according to exact specifications. The text notably describes the Ark as a giant cube—measuring 120 cubits in height, width, and length—unlike the elongated, boat-shaped ark of the Hebrew tradition. Some sources refer to this vessel as a šuruppak. Utnapištim seals it with pitch and designs it to endure the impending deluge. Following Enki’s guidance, he brings aboard his family, skilled workers, supplies, and representatives of all animal species, thereby preserving life for the world to come.

The Deluge and Its Aftermath

The flood narrative follows a rhythm familiar to readers of later Abrahamic traditions. For six days and six nights, the storm rages with devastating force. The seventh day brings silence. The world lies submerged beneath the waters, save for the single vessel that carries the remnants of life. This numerical motif of six and seven days likely reflects ritual and cosmological symbolism in Mesopotamian thought.

Eventually, the waters begin to recede. The Ark comes to rest atop Mount Nisir—a location sometimes identified with modern-day Pir Omar Gudrun in Iraqi Kurdistan. To determine whether the land has become habitable, Utnapištim releases a series of birds: first a dove, then a swallow, and finally a raven. The raven does not return, suggesting that it has found dry land and confirming that the earth is again capable of sustaining life.

Upon disembarking, Utnapištim offers sacrifices to the gods. The deities gather “like flies” around the offering, drawn by its aroma and the act of devotion. Enki and the other gods rebuke Enlil—once wrathful and uncompromising—and urge him to consider mercy and proportional justice. Enlil eventually relents and grants Utnapištim and his wife the gift of immortality. The gods then send them to a remote, paradisiacal region “at the mouth of the rivers,” a symbolic realm beyond mortal reach, where they serve as the eternal guardians of human memory and wisdom.

Parallels with the Biblical Account of Noah

The similarities between the Utnapištim narrative and the Noah story in Genesis chapters 6–9 are striking and have long been a focus of scholarly attention. Both protagonists are deemed righteous in the eyes of the divine. Both receive instructions to build an ark to escape a flood sent to cleanse the earth. In both stories, animals are gathered in pairs or groups to repopulate the world. Both narratives involve the release of birds to test the retreat of the floodwaters, and both conclude with a sacrificial offering that elicits divine favor.

While there are notable theological and literary differences—the Mesopotamian account involves a polytheistic pantheon with internal conflict, whereas the Biblical version presents a monotheistic, moralistic framework—the structural and thematic overlaps suggest a shared narrative heritage. Many scholars propose that the flood tradition in Genesis was influenced, directly or indirectly, by older Mesopotamian sources, likely transmitted through oral or scribal contact during the Babylonian exile in the 6th century BCE, when Judean elites were exposed to Mesopotamian literature and cosmology.

Historical and Geological Hypotheses

Beyond literary and religious analysis, various scholars have speculated that these flood narratives may reflect collective memories of real geological events. Theories range from localized river flooding in Mesopotamia—particularly along the Tigris and Euphrates—to the hypothesized inundation of the Black Sea basin around 5600 BCE, when rising Mediterranean waters may have breached the Bosporus and submerged vast coastal settlements. Another possibility is the climatic upheaval that followed the last Ice Age, during which melting glaciers caused significant sea level rise and possibly traumatic flooding events across Eurasia.

While these hypotheses remain speculative, they underscore the deep resonance of flood motifs across human cultures. Nearly every ancient civilization—from Mesoamerica to India, from Greece to Sub-Saharan Africa—possesses some version of a flood story, suggesting that the psychological and existential impact of environmental catastrophe was woven into the mythic imagination of early societies.

Conclusion: The Legacy of Utnapištim

The tale of Utnapištim is not merely a mythological curiosity; it is a foundational narrative within ancient Near Eastern literature that reflects enduring themes of divine justice, human vulnerability, and the fragile continuity of civilization. Its preservation on clay tablets and its transmission across cultures attest to the central place of the flood myth in the early human effort to explain suffering, resilience, and the boundaries of divine power.

Though eclipsed in popular consciousness by the more familiar story of Noah, Utnapištim remains a profound symbol—not only of survival but of forbidden wisdom and divine-human dialogue. As modern scholarship continues to explore the intersections of myth, history, and archaeology, the legacy of the Mesopotamian flood narrative continues to inform our understanding of humanity’s oldest fears and aspirations.

References

George, A. R. (2003). The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts. Oxford University Press.

Lambert, W. G., & Millard, A. R. (1969). Atra-Hasis: The Babylonian Story of the Flood. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Dalley, S. (1991). Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others. Oxford University Press.