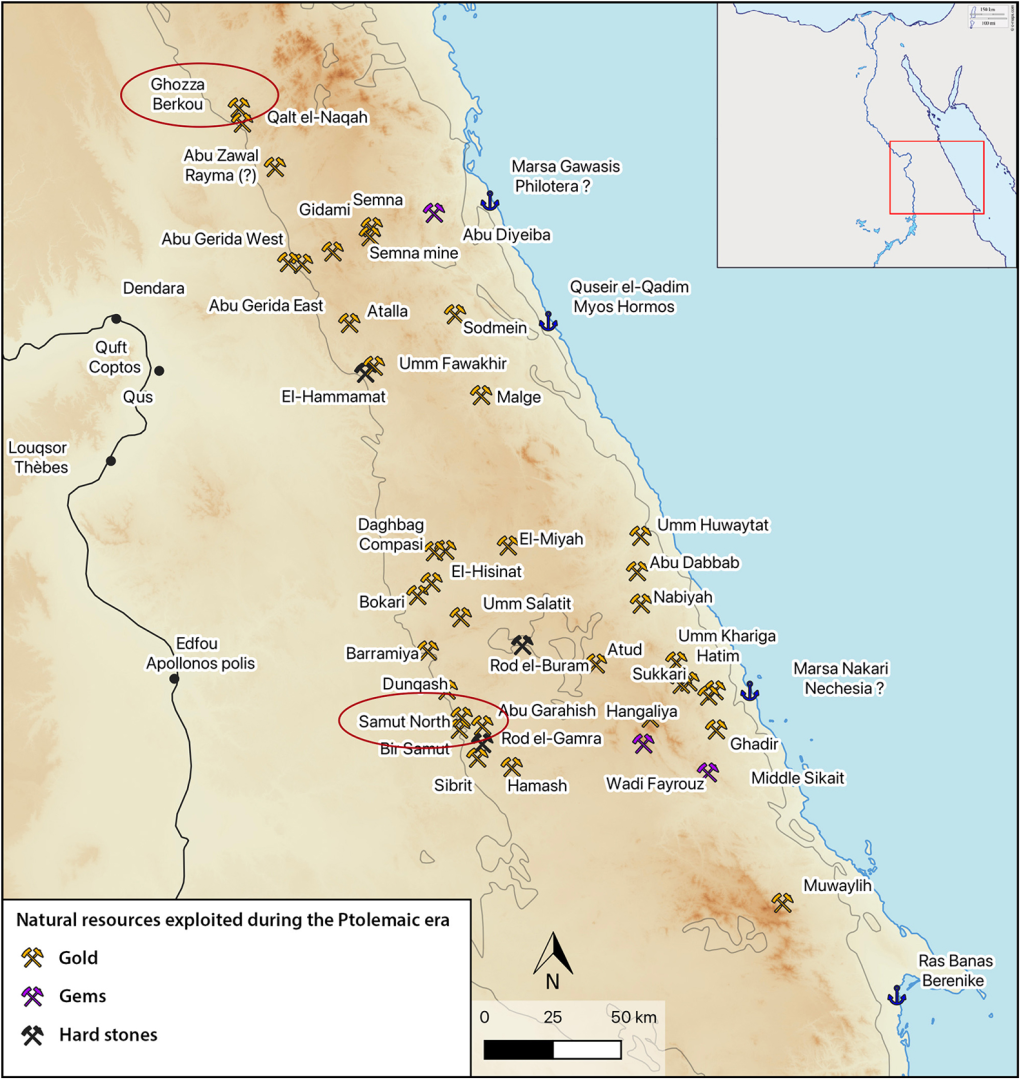

Egypt’s Eastern Desert has long been synonymous with gold. This precious metal, highly coveted throughout history, reached new heights of extraction during two key periods: The New Kingdom (c. 1500–1000 BC) and the Hellenistic era (332–30 BC). Following Alexander the Great’s conquest of Egypt in 332 BC, the Ptolemaic dynasty opened nearly 40 gold mines to fuel their ambitions—funding military campaigns, monumental construction projects in Alexandria, and displays of power across the Mediterranean. Among these early mining sites was Samut North , excavated by a French team in 2014–2015, which provided valuable insights into the harsh realities of ore production during this time.

But recent discoveries at another site, Ghozza, are offering even deeper insights into the complexities of labor and life in ancient Egyptian gold mines, while also revealing some unsettling truths about forced labor under the Ptolemies.

The Rise of Ptolemaic Mining

Gold was the lifeblood of the Ptolemaic economy. After founding his dynasty, Ptolemy I needed vast resources to solidify Egypt’s dominance in the Mediterranean world. To achieve this, he turned to the mineral-rich Eastern Desert, where almost 40 mines were established or reactivated during the Early Ptolemaic period. These operations not only supplied wealth but also symbolized the dynasty’s prosperity and ambition.

One of the earliest known mines from this era is Samut North , located deep within the desert. Excavations revealed that it operated for just four to five seasons between 310 and 305 BC, each lasting six to nine months. The workforce here appears to have been tightly controlled, living in guarded dormitories while processing quartz using large collective grinding mills. While Samut North provides a glimpse into industrial-scale mining, its short lifespan raises questions about sustainability and working conditions.

Ghozza: A Mining Village Unlike Any Other

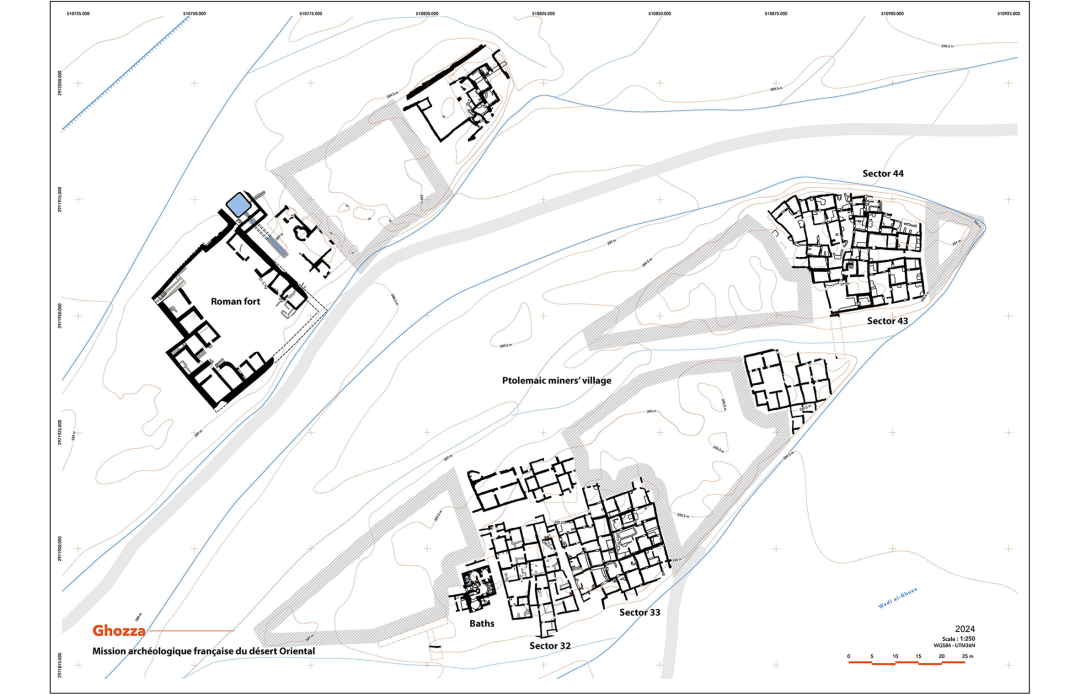

Fast forward to 2020, when archaeologists began exploring Ghozza , the northernmost Ptolemaic gold mine. Located further north than Samut North, Ghozza offers a stark contrast in terms of organization and social structure. Two major occupation phases have been identified, likely spanning several years during the second half of the third century BC.

Unlike the rigid setup at Samut North, Ghozza resembles a small village. Complete with residential blocks, streets, administrative buildings, and even baths. This layout suggests a different dynamic, one where workers may have enjoyed greater freedom and mobility. Handwritten records etched onto pottery shards, known as ostraca, reveal details of daily life. Including evidence that some miners received wages. Combined with the absence of guarded buildings, this points to a diverse workforce. Possibly composed of free laborers alongside others subjected to less restrictive forms of control.

However, not all was as it seemed. In January 2023, excavations uncovered something chilling: iron shackles.

Shackles and Forced Labor

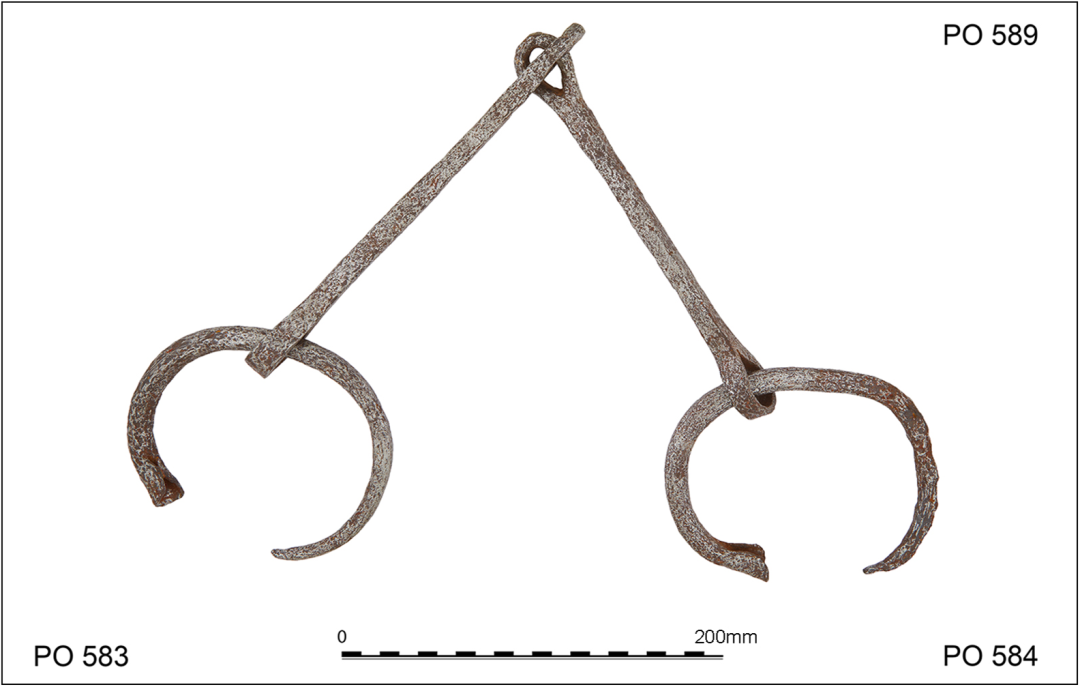

In Sector 44, a storage and food preparation area on the eastern edge of the village, archaeologists discovered two sets of iron shackles. One set, consisting of seven foot-rings and two articulated links, was carefully arranged in a pit beneath the floor of a corridor. Another partial set, scattered across a room filled with iron objects, included fragments of rings and links. These artifacts tell a grim story.

Analysis confirms that these shackles were designed specifically for humans—not animals, as rope ties were typically used for livestock. When closed around a person’s ankles, they would have restricted movement without assistance, making walking slow and exhausting due to their weight. Yet, unlike modern handcuffs, they left hands free, allowing prisoners to perform physical tasks like mining.

This discovery aligns with ancient texts describing the brutal conditions endured by miners under the Ptolemies. Agatharchides, a second-century BC writer quoted by Diodorus Siculus, vividly recounts how prisoners of war and convicted criminals worked ceaselessly day and night, their feet bound in chains. While Agatharchides’ accounts are literary, the Ghozza shackles provide tangible archaeological proof of such practices.

What makes this find particularly remarkable is its rarity. Shackles from antiquity are rarely documented in Egypt, let alone in mining contexts. The Ghozza examples are among the oldest ever found in the Mediterranean region. Predating similar finds from Europe’s Late Iron Age and Roman periods. They closely resemble those discovered in Greece’s Laurion silver mines in the 19th century, suggesting cross-cultural exchanges in both technology and methods of labor control.

Cross-Cultural Connections in Mining Technology

The parallels between Egyptian and Greek mining techniques extend beyond shackles. Quartz-grinding mills at Samut North bear striking similarities to those at Laurion, indicating that Greek and Macedonian engineers brought advanced knowledge to Egypt under the Ptolemies. This technological transfer underscores the interconnectedness of the Hellenistic world, where innovations in one region influenced practices elsewhere.

Yet, while these advancements boosted productivity, they came at an immense human cost. The grandeur of Ptolemaic Egypt, with its towering monuments of Alexandria and glittering treasures of the court, was built on the backs of exploited workers, many of whom endured unimaginable hardships.

Conclusion: Beneath the Glitter Lies a Dark History

The discovery of shackles at Ghozza forces us to confront the darker side of Egypt’s golden age. While the bustling village-like environment hints at a degree of freedom for some workers, the presence of restraints reminds us that others were far less fortunate. As excavations continue, researchers hope to uncover more clues about the lives of these individuals, including whether specific areas of the site served as containment zones.

For now, the Ghozza findings serve as a poignant reminder of the human toll behind ancient Egypt’s glittering wealth. Beneath the imposing mountains of the Eastern Desert lies a history of exploitation—a stark contrast to the opulence celebrated in historical narratives. The gold extracted from these mines funded the ambitions of rulers, but it came at a price paid by countless unnamed workers.

References